Africa’s Sh905 billion book industry faces challenges despite growth potential - UNESCO

The continent’s young population is driving a surge in demand for textbooks, teacher guides, and learning materials. However, local publishers are unable to keep pace.

Africa’s book and publishing sector, currently valued at around US$7 billion, could more than double to US$18.5 billion if governments and institutions invest strategically, a new UNESCO report shows.

Educational publishing alone has the potential to contribute US$13 billion, highlighting a significant opportunity in a continent with one of the world’s youngest populations.

More To Read

- Publishers plead with State to remove 16 per cent VAT on books

- Kenya Publishers Association honours Ngugi wa Thiong’o with Hall of Fame induction

- Publishers warn of delays in Grade 10 textbooks rollout over Sh3 billion government debt

- Beyond 'Kifo Kisimani': Inside the mind of Kenya’s literary titan, Prof Kithaka wa Mberia

- UNESCO urges dialogue as world marks day for remembrance of slave trade, abolition

- Nairobi book vendors decry City Hall's backstreet relocation directive

The report, The African Book Industry: Trends, Challenges and Opportunities for Growth, provides the first comprehensive overview of publishing across all 54 African countries.

Despite its intellectual vibrancy and large youth demographic, the continent remains heavily dependent on imported books, while local publishing struggles to meet demand.

According to UNESCO, Africa imports about US$597 million worth of books annually but exports only US$81 million, resulting in a trade deficit of 76 per cent. South Africa, Kenya, Egypt, Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, and Senegal are regional leaders in book exports, but most African countries rely on publishers from Europe, particularly France and the United Kingdom.

Education and youth demand

The continent’s young population is driving a surge in demand for textbooks, teacher guides, and learning materials. However, local publishers are unable to keep pace. Public procurement policies frequently favour international companies over local firms, despite local publishers’ better understanding of African languages, cultures, and educational needs.

Universities sidelined

The report highlights a striking absence of African universities in content creation. While these institutions shape curricula and train future leaders, most rely on foreign publishers. University presses, once crucial for producing local textbooks and scholarly work, are underfunded or have closed entirely.

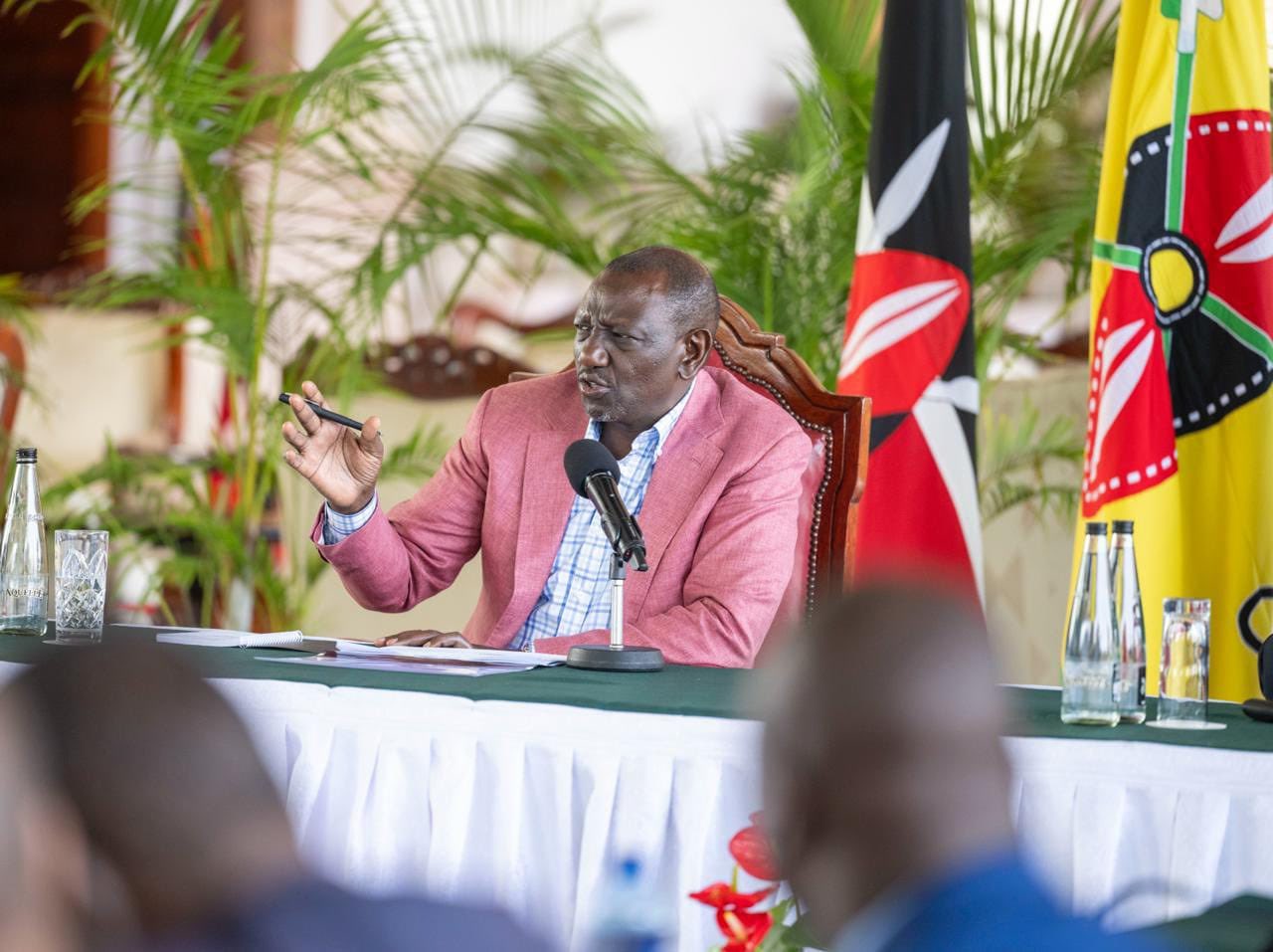

“In my view, African universities have largely been absent from local publishing conversations because of a lack of a commercial mindset: universities are run by academics who lack the skills to generate revenue. There is a need for a commercial arm in universities to tap into available opportunities. The first practical step that could change this is to set aside ideological issues and focus on strategic business thinking,” said Kamau Kiarie, chairman of the Kenya Publishers Association.

Kiarie emphasised that government support is essential for universities to reclaim their role in educational publishing.

“Without dedicated investment, these presses cannot meet the capital-intensive demands of modern book development, which includes everything from research and editing to printing, marketing, and distribution. Reviving them will require a deliberate financial injection from governments as part of a long-term strategy to build local publishing capacity.”

Only South Africa and Nigeria maintain relatively strong university publishing platforms, while most other countries have lost the ability to produce peer-reviewed books, academic journals, or scholarly monographs internally.

Dependency on the Global North

As foreign publishers expand their digital and open-access platforms, African universities struggle to produce or distribute their research.

This dependence not only reduces global visibility for African scholarship but also entrenches reliance on the Global North for academic legitimacy.

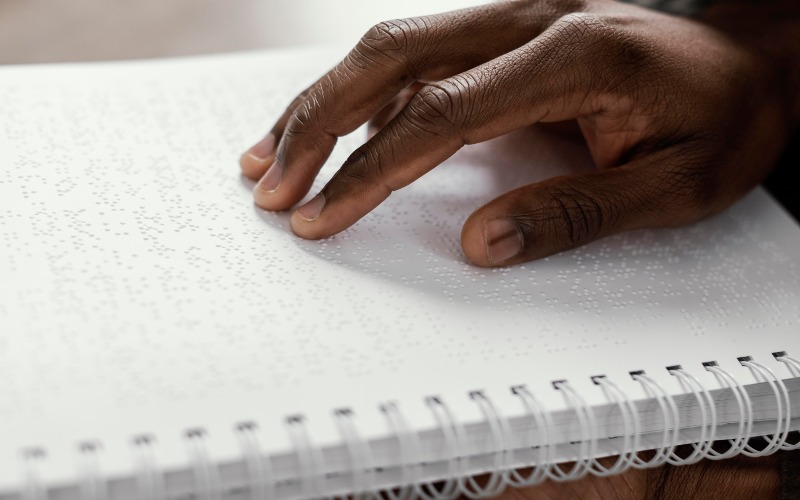

Imported materials often fail to reflect African languages, histories, and social contexts, weakening the relevance of education.

UNESCO data show that only 38 per cent of African countries have a dedicated department or council for books and publishing, and ISBN agencies operate in just 54 per cent of nations, making trade and tracking challenging.

Many countries lack modern copyright laws or publishing strategies. Only five - Algeria, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, and Mauritania—have enacted publishing-specific legislation beyond basic legal deposit and copyright rules.

Digital tools and partnerships

Kiarie recommended strategies to strengthen local publishing: “African academics and institutions can start reducing their reliance on foreign journals and publishers by strategically investing in locally driven systems that emphasise both quality and reach.

“First, universities and presses need to offer meaningful incentives to authors, especially academics, through fair, predictable, and timely royalties.

“Many African scholars are willing to publish locally, but they must see that their intellectual labour will be properly rewarded. Second, partnerships with established university presses in the

Global North, such as Oxford University Press or Cambridge University Press, can provide valuable mentorship, technical expertise, and collaborative publishing models.

“These relationships can help African presses implement proven strategies while retaining ownership of local content. Third, African institutions must fully harness the power of modern technology. Digital tools can significantly reduce production costs, accelerate workflows, and expand access to global audiences via online platforms.

Artificial intelligence, for example, is largely underused in African universities, yet it could streamline book development, editing, and translation processes.”

Africa’s linguistic diversity is poorly represented, with over 2,000 indigenous languages overshadowed by English, French, and Portuguese. Weak local printing capacity also forces publishers to outsource production abroad, increasing costs and reducing competitiveness.

More than half of African countries apply standard VAT on books, making them more expensive and less accessible. Some countries, including Botswana, Ghana, and Mauritius, have introduced supportive models for writers and publishers, but these remain exceptions. Other hurdles include limited library access, a shortage of skilled workers, and weak infrastructure.

Digital innovation is helping transform publishing. In Senegal, Nouvelles Éditions Numériques Africaines, and in Ghana, Akoobooks, are expanding e-books and audiobooks, while Librairies du Maroc is widening digital access.

Despite these advances, Global North publishers still dominate African academia. Scholars often publish abroad to secure grants, recognition, and career advancement.

“Universities need to adopt a model of collaboration and partnerships with like-minded organisations to handle these large publishing projects. Such organisations include, but are not limited to, United Nations agencies like UNICEF, UNESCO and many others.

If African universities are serious about self-determination, academic freedom, and relevant education, then investing in publishing is not optional. It is fundamental,” Kiarie said.

Publishing abroad also creates a “brain drain” in knowledge, where African content is filtered and monetised externally before being sold back at high prices. While UNESCO stops short of calling this exploitative, the implications are clear: Africa’s knowledge economy is shaped and monetised outside the continent.

Kenya is a notable exception, with a strong book policy and copyright protections. Its publishing sector is relatively vibrant, though challenges such as piracy, uneven enforcement, and bureaucratic hurdles persist.

Top Stories Today